The Japanese Art Of Acceptance: Embracing Vulnerability

Failure to do anything at a crucial moment in life can prevent us from taking the crucial step to an incredible experience. Admitting your own vulnerability is courageous and a prerequisite for strengthening your resilience.

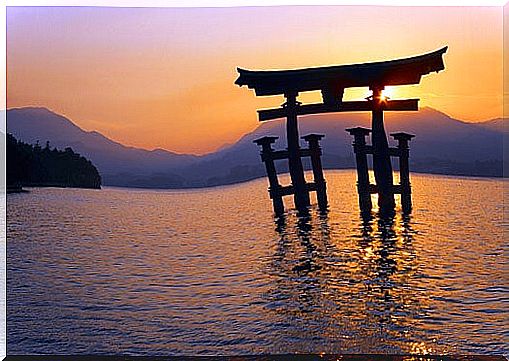

There is a term in Japanese that gained popularity during World War II. This term has been used more frequently since the March 11, 2011 tsunami. “Shikata ga nai” means something like “we can do nothing”.

“Honesty and sincerity make you vulnerable. No matter what, always be honest and sincere. “

Holy Mother Theresa of Calcutta

The Japanese understand this expression very differently than it probably sounds to most Westerners, namely negative and hopeless. The Japanese attribute a more useful and dignified meaning to it: When life is unfair, anger or anger is of no use. Nor is it useful to get caught up in your own suffering by constantly asking yourself: “Why me, how did I deserve it?”

Acceptance is the first step to liberation. You can never get rid of all pain and suffering, that is clear, but if you accept what has happened to you, you can regain something essential that enables you to look ahead: the will to live.

“Shikata ga nai” or the power of vulnerability

Since the 2011 earthquake and the subsequent nuclear disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant , many Western journalists have been traveling to northeastern Japan to see what this tragedy has caused and how the people there are coping with the disaster. It is fascinating to see how they deal with their losses and this radical turning point in their lives.

The journalists take home more than just a report. You achieve more than just interviews and photos. They experience wisdom and return to their everyday western life with the feeling of an inner change. An example of the impressive bravery is provided by Mr. Sato Shigematsu, who lost his wife and son in the tsunami.

Sato Shigematsu writes a haiku every morning. This is a poem about nature or everyday life that consists of three verses. Mr. Schigematsu finds great comfort in this morning routine and likes to show journalists his haikus, such as the following:

“Without belongings, naked

But blessed by nature Caressed

by the breeze that heralds summer.”

As the tsunami survivor and victim at the same time explains, the value of this morning routine is to connect with yourself for healing, as nature does. He also explains that life is uncertain and sometimes ruthless. Occasionally it could even be cruel. To accept what has happened and to say “Shikata ga nai” to himself , however, enables him to alleviate his suffering so that he can concentrate on what is necessary, on building a new life for himself.

“Nana korobi, ya oki”: If you fall seven times, get up eight times

“Nana korobi, ya oki” means something like “if you fall seven times, get up eight times” and is an old Japanese expression. It perfectly reflects that ideal of resilience that is so ingrained in Japanese culture. We can see this resilience in their sport, in the way they do business, in the way they focus on education, and also in their art.

The wisest and strongest warrior is aware of his own vulnerability.

This resilience has important nuances. Understanding these can prove very useful and enable us to deal with adversity in more effective ways.

How vulnerability can increase our resilience

According to an article in the Japan Times newspaper , admitting vulnerability leads to positive changes in the body. The blood pressure drops and we feel less stressed. Coming to terms with tragedy, admitting to your vulnerability and accepting your pain is a way of letting go and accepting what you can’t change for what it is.

- After the tsunami, most of the survivors helped each other according to the motto “ganbatte kudasai”, meaning “we must not give up”. The Japanese understand that you have to accept the situation you are in and make yourself useful to yourself and others in order to overcome a crisis.

- Another interesting aspect is their perception of calm and patience. The Japanese know that everything takes time. Nobody can recover from one day to the next. Healing a broken heart takes time, a lot of time. Rebuilding a village, a city and an entire country also takes time.

We need a lot of patience, prudence and perseverance. Because no matter how often life or nature knocks us to the ground with its disasters, we will never give up. Humanity is resilient and will continue to exist. So let’s learn from the wisdom that Japanese culture gives us.