The Forgetting Curve

At the end of the 19th century, Hermann Ebbinghaus was the first to systematically research how we forget things over time. We are all aware of this phenomenon and for this reason we repeat the information that we want to remember so that it is not forgotten. A curious fact is that Ebbinghaus himself was the subject of his study. He wanted to research scientifically this phenomenon that we all experience. By experimenting on himself, he was able to define what we now know as the forgetting curve. And we all travel along that forgetting curve, although perhaps we shouldn’t explain the process that way.

Ebbinghaus studied at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Bonn, where he received his doctorate in 1873. While Ebbinghaus developed his competencies as a researcher, he always believed that quantitative analysis methods were applicable to higher-level mental processes. That is, Ebbinghaus assumed that there are ways to measure parameters in psychology. He didn’t think twice about using a variable that we use in a lot of measurements: time. In this case the time to forget.

He conducted a number of reliable experiments using the monitoring tools available at the time. It was his intention to describe our memory function based on a number of laws. For example, he carried out a test called the recall test. The test is based on repeating idioms from which some words are intentionally left out.

Ebbinghaus hoped that he would learn something about the nature of learning and forgetting. He also wanted his research to have practical value in the field of education. However, many critics of his work felt that he shouldn’t have focused so much on repeating words. They believed that he should have explored how memory works in everyday situations. They also countered him by stating that his results were perfectly reproducible under controlled laboratory conditions, but not in real life. In real life, our memories work under conditions that are difficult to replicate in the laboratory. One must also consider motivation, inadvertent repetition, and the emotional impact on remembering and forgetting.

Some of his most important works are On Memory: Studies on Experimental Psychology (1885), On a New Method for Testing Mental Ability and Its Use in School Children (1897) and Fundamentals of Psychology, Volume One (1902) and Volume Two (1908). Before we talk about its forgetting curve, let’s outline some fundamentals about memory and learning. This should help to better understand the meaning of the forgetting curve.

What is learning

It is not easy to formally define learning. There are many different opinions on how to do this. Each highlights a different facet of this complex process, but many definitions refer only to observable behavior. Another definition of learning touches on the state of inner consciousness.

Both aspects, i.e. observable behavior and internal states, are important. Both are compatible with current learning theory, according to which we can define learning as follows: Learning is a change in the mental state of the organism. This change is the consequence of experience. And it influences the organism’s potential to adapt to change.

The work of Ebbinghaus

The description of the laws of association has directly influenced the theories on learning. There is no better example of this than that of Ebbinghaus’s work. According to Ebbinghaus, we can better associate two mental events if we use stimuli that are free from other associations. So in order to work with stimuli that have so far had no meaning, Ebbinghaus used “useless syllables”. Syllables such as BIJ or LQX, which, according to Ebbinghaus, were of no relevance to the test subject.

So he tested the principles of association that were defined more than 100 years before Ebbinghaus’ work. For example, he compared the strength of the association between two stimuli that were written down once next to each other and two that were notated far apart. In this way he was able to reinforce many of the ideas first proposed by British empiricists. They theorized that proactive associations were stronger than retroactive ones. So if the syllable BIJ precedes the syllable LQX, then BIJ is more capable of triggering the memory than LQX. Interesting, isn’t it?

In order to learn to learn, one has to understand memory and therefore also know the forgetting curve. Don’t forget that without memory, learning wouldn’t be possible. Any implementation of a learned reaction requires the memory of a past practice or implementation. Everything we remember and what we learn goes through three phases: encryption, storage and retrieval:

- In the first phase of learning, we encrypt the information. We translate them into the language of the nervous system and make room for them in our memories.

- By storing, the information or knowledge is retained over time. In some cases this phase is relatively short. For example, information only remains in short-term memory for about 15-20 seconds. In other cases, the storage can last a lifetime. This type of storage is called “long-term memory”.

- After all, the retrieval is the phase in which we remember the information and respond. We show what we have learned before – and what we still know today.

If the implementation is just as appropriate as with the acquisition, that speaks for minimal forgetting. However, if the implementation is far less satisfactory, then we’ve forgotten. Sometimes it is easy to measure how much time it took you to lose a certain part of something that you had previously encrypted.

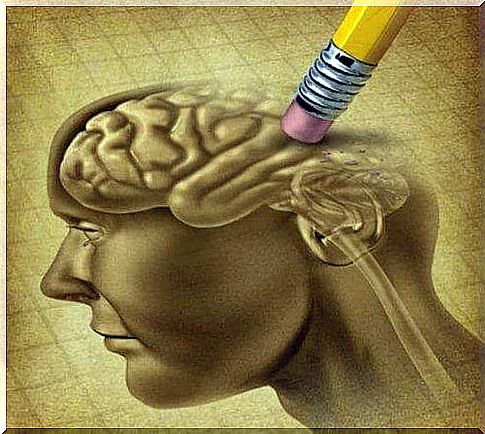

Why do we forget

Understanding why memories remain after we encrypt them is a major challenge for psychologists. They also want to understand why we forget things after learning. There are several ideas that try to answer these questions.

Storage theories

Some theories of storage focus on what happens to the information during the storage phase. For example , the theory of decay assumes that we forget because memories are weakening. Their strength decreases during the storage period, like footprints on a sandy beach. There is evidence to support this theory. However, modern theorists describe forgetting more in terms of memory loss.

In addition, the theory of interference states that we forget because we overwrite, because we acquire new information that competes with others as it is stored. For example, acquiring new information makes us forget old information. This is called retroactive interference. At the same time, the presence of old information can have a positive or negative effect on the retrieval of recently formed memories. This is called proactive interference. For example, we remember someone’s phone number better if it is similar to our own. However, if our number contains an “847” and that of the other has an “874”, the probability of number spinning is very high.

Theories of retrieval

Retrieval theories are that we forget because we fail during the retrieval phase. This means that the memory “survives” storage, but the person cannot access it. Imagine looking for a book in a library that was sorted incorrectly. The book is in the library (the information is intact) but we cannot find it (information is not available). Many recent studies on memory support this theory.

Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve

The passage of time appears to have a negative impact on storage capacity. As we mentioned earlier, Ebbinghaus was the first to systematically research memory loss over time. He described what we know today as the “ebbinghaus curve”. The concept of a “curve” refers to a graph that he drew as a result of his research.

We know that his study lists consisted of 13 syllables. He repeated these lists until he could reproduce them twice without errors. He then rated his ability to retain the information at time intervals ranging from twenty minutes to a month. He based his famous forgetting curve on the results of these experiments.

It was about clarifying how long we can keep information if we don’t repeat it. The results of his study showed that we forget a lot even at the shortest intervals. In addition, Ebbinghaus found that meaningless information that is free of association makes it easier to forget. At first we forget a lot and later more and more slowly. If we plot this information on a graph, we see that the curve is logarithmic.

A typical forgetting curve shows how within a few days or weeks we forget most of what we have learned. This happens when we don’t make an effort to repeat the information. At the same time, Ebbinghaus found out that repetition is useful: If we want to memorize something, the first repetition should perhaps take place an hour after the first study. That way we can put off the next rep longer.